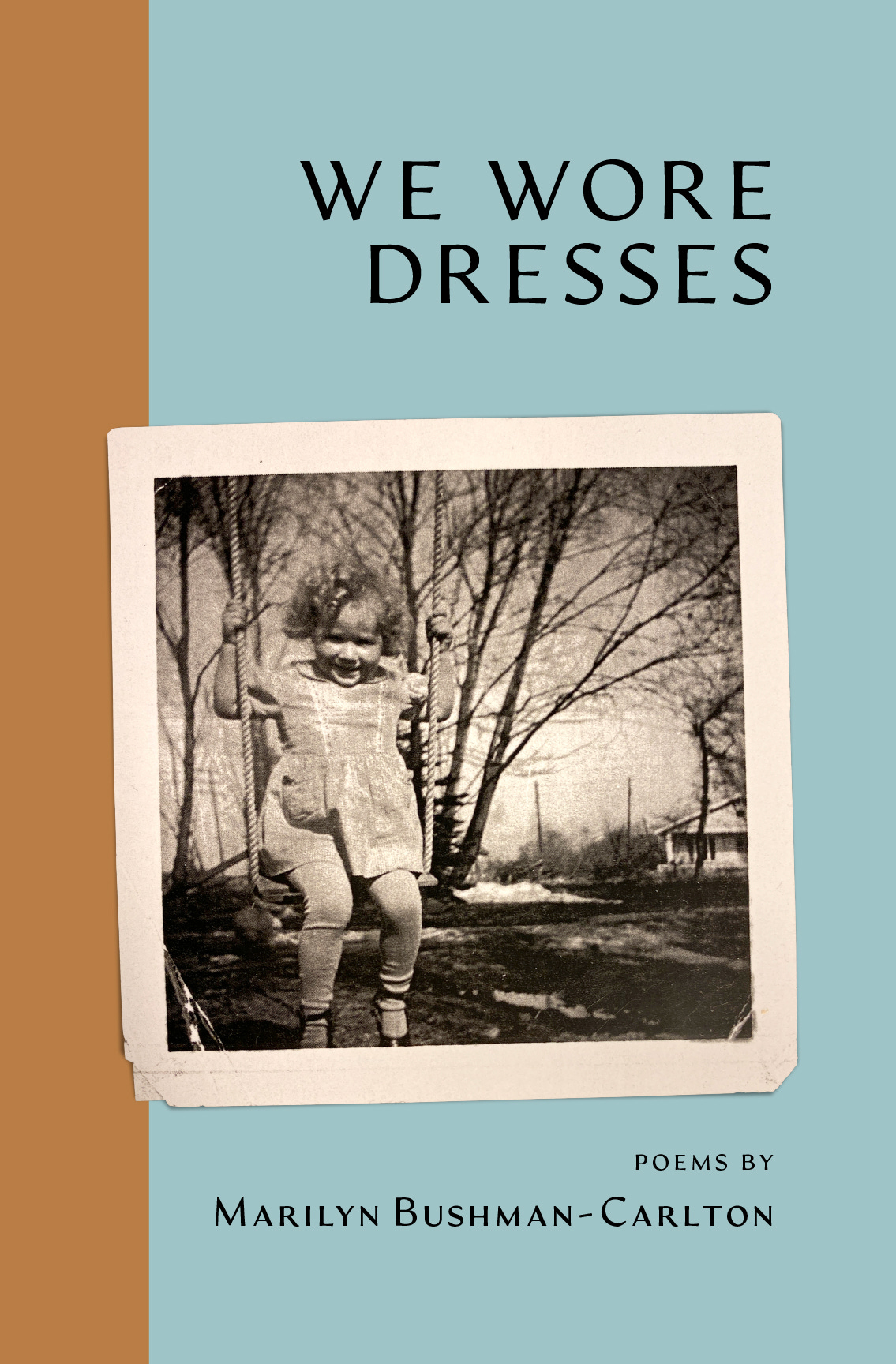

We Wore Dresses

Poems by Marilyn Bushman-Carlton

In this book of poetry, Marilyn Bushman-Carlton explores how girls her age “learned the lay of the land” and the “dead-end streets” wearing dresses. There was no “scrabbling to the rescue” or “scorching to home base” for girls. Rather, wearing “angel trumpet, fuschia, and inverted tulip” dresses, they played jacks, with “bouquets of skirt bunched in the V of their legs.” To long elegant versions, perfumed orchids were “pinned carelessly close to [their] hearts.”

We Wore Dresses is the metaphorical score behind her subsequent investments in marriage and motherhood, years crescendoing with self-awareness, a resolute love for her husband and children, and a dedicated feminist voice even as grandchildren come along to “climb as high as [they] dare,” and whose turn it is to “trip into the summer grass of their enormous lives;” to make the world both “small again…and possible.”

In a poem near the end of Marilyn Bushman-Carlton’s We Wore Dresses, the speaker says, “I’m digging out, making room for extravagant abundance / of nothing at all, for the sharper relief of absence” ("The Solace of Letting Go"). There is, however, a delicate blueprint by which we arrive at this sly renunciation. The poems earlier in the collection show in unsparing terms how girlhood shapes womanly experience; they are indispensable for reading the later poems, more yielding and open. The book is a cabinet of wonders: even the poems that render the most painful moments of the soul’s—and body’s— progress gleam with magical naming. In “Murmuration,” the speaker, witnessing starlings weaving their patterns in the sky, says, “All hail and hallelujah I say to no one / & divine what I can from these ordinarily / misbehaving birds, praise their bonanza / of magnetic plainsong”. I am drawn to and enlivened by these generous, musical, sharp poems.

—Lisa Bickmore, Poet Laureate, State of Utah

Marilyn Bushman-Carlton's fourth poetry collection, We Wore Dresses, is the work of a mature artist completely in command of her craft. These poems explore every stage of the poet's life from girlhood to retirement and every relationship from daughter to wife to mother to grandmother with compassion, elegance, and wit. This work is not to be missed.

—Holly Welker, editor of Baring Witness: 36 Mormon Women Talk Candidly about Love, Sex, and Marriage and Revising Eternity: 27 Latter-Day Saint Men Reflect on Modern Relationships

Marilyn Bushman-Carlton offers these poems like seashells on the palm of a child at the beach for the first time, glimmering in their tender specificity. A young girl plays on the “tricky bars.”A mother is touched when her young adult son wants to watch again a movie with her that she introduced him to as a child. A group of young parents learn from a Sunday School teacher who has lost an arm. A woman in an aging body contemplates whether to give up her manicures. And here, too, are many fascinating landscapes—St. George, France, Ethiopia, an old-fashioned bathroom. The collection is a mosaic of moments—delightful, rueful, nostalgic, poignant. But the real joy is in how we get to the universal through these specifics—the tutelage of childhood, living in a body, cultural expectations and restrictions. After reading, I feel as if I’ve had a long sanity walk with a good friend, the kind you can empty yourself to and who helps you pick up each concern and turn it to the light.

—Darlene Young, author of Count Me In, Here, and Homespun and Angel Feathers; winner of the Association for Mormon Letters Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Field of Mormon Letters

We Wore Dresses is a rich collection of poems, full of Marilyn Bushman-Carlton’s wisdom. The collection demonstrates that she has lived well and loved enormously. It begins by examining what was both endearing and annoying for girls growing up in the 1960s (dresses always; physical “exercise” that kept girls weak; wanting to be thin like Audrey Hepburn, Jackie Kennedy and Twiggy; MIA girls being made responsible for boys’ sexual behavior; and hoping to find something in life to be good at). But the collection goes much farther than its title subject. The poems show continual growth and exploration for Marilyn and her family, and they embody great love and insight. The true partnership Marilyn and her husband share is demonstrated in several poems, especially “Statistics Say You’ll Die First.” Family poems abound, and there are some I will remember for the rest of my life. The poems are also superbly wrought, with lines like “lizards and toads lead lower-case lives” and “the faintest ripple a spilling whisper / a soap bubble dispersing” to describe a quickening baby in her womb.

This is a collection that is meant for reading and rereading, with new rewards each time it is experienced.

—Susan Elizabeth Howe, author of Infinite Disguises

From the author:

I don’t deliberately write Mormon poems so I was somewhat surprised at how Mormon my book became as the final assortment came together for this collection. Mormon, not in a moralizing sense but a cultural one. As the late Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye says in her essay introducing Epistles to the Saints, “The Church is mostly not church. It is mostly what people do in their everyday lives and relationships.” My poems reflect the Mormon way of doing and being simply because it’s what I know. And I don’t know of any other culture that does so many things simultaneously and/or better than Mormons do.

The title poem of We Wore Dresses was not the first poem I wrote for the collection, but writing it gave me both a metaphor and a theme for the book. In the small Utah County town where I grew up, church and community bled together like a red shirt in the wash, and I do mean red as in conservative and shirt as in patriarchal. Of course, we all know the gender roles both church and society embrace and how women’s roles are most often defined by our bodies: how we, and others see, treat, and present them. We presented in dresses that defined our bodies’ uses, what we could and could not do. We couldn’t play on the tricky bars, for example, without fear of exposing underwear approximate to our girl parts. For boys, too, it was taken for granted that they embrace their boy roles. Those roles can be glimpsed in my book as well.

I like to think of girls confined to wearing dresses as the score in the background of my formative years. And that score, of course, has played on and on throughout my long life. In poems it plays as I work at jobs rather than go to college, as I marry, have five children in quick succession, am a stay-at-home mom. It plays in what I eat, how and what decisions I make, and behind my role as wife of an attorney.

The second phase of the Women’s Movement began at about the time I married my childhood sweetheart, and to both of us, equality made perfect sense. Society was beginning to change for both women and men, and we welcomed what some in the church considered radical ideas. Some of the poems show both my struggles to define myself and my husband’s—the back and forth of establishing equity in a partnership that gives primacy to both his profession and overall importance.

Although I’d embraced motherhood and homemaking wholeheartedly, a light came on when I read Betty Friedan’s description of “the problem with no name,” (The Feminine Mystique), the persistent feeling that something, a big something, was missing in my life. I had no idea who I was or what I needed. It was my husband’s suggestion that I go to college, and with his full support and encouragement, I became a student for the first time at the University of Utah the same year our youngest child began kindergarten. I knew my family could not be secondary, but I also knew I wanted an education badly and would give it my all. The pressure was on. My ability to take classes was a family thing—everyone had their jobs—that usually ran as smoothly as a lunch line.

The earlier poems in the collection have an edge as I look back at a time when I was actually exquisitely happy. I’d loved my formative school years, loved being a girl and living in a girl world with its intimate girl friendships. I enjoyed playing jump rope and jacks and had no desire to do boy things like sports. I’d had no idea that even then, as a female, I’d been considered secondary and had been “put into a dress” to keep me in my prescribed role.

Simone de Beauvoir (The Second Sex) says that “One’s life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of others by means of love, friendship, indignation, and compassion.” I love how she slipped indignation in among the expected womanly things. I cringed when I began to date and boys felt the need to show me how to hold a golf club or throw a bowling ball. Or when my husband-to-be insisted that I agree he would make the big, final decisions (I finally agreed but my fingers were crossed.) Again, from Beauvoir: “To make oneself an object, to make oneself passive, is a very different thing from being a passive object.” From as long as I can remember, I’ve recognized each and every insult to my full humanity, and that shows up in my, sometimes snarky, writing. Mostly it shows up in the poems about my growing-up years as I look back at that time with the wisdom of experience.

Of course, I spent most of my life adjusting my schedule to my husband’s, writing at home as I managed the household, both occupations not easily identified; and the latter unending. I reclaimed my maiden name with a simple hyphen, and began telling my story. I found my identity by writing myself into existence.

Like Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, my art often originates from my world at home, where I try “to catch the fleeting moment—anything, however small.” (Morrisot) My family are ready subjects. My poems are about what I did, and do: being in a marriage and being a mother, often musing about whether I did this or that thing right. In “Music Comes for the Oldest Son,” that son “comes to the symphony lugging his polished shoes, his pockets bulging with woe,” while I worry he is “bankrupting [my] best efforts to indulge [my] vanity” as I’ve gussied [the five children] to flawlessness.” About that same son, I wonder in a poem after the fact how my feminism might have affected his early years.

The dress is like wearing a sign or a logo that says “girl.” It decrees what paths we follow, how we envision ourselves. It insists that some things don’t come in your size or shape. It says the things on this side of the room are okay for you to use, but don’t touch the things on the other side. It says you are hobbled from even seeing yourself in a variety of roles. What executive wears, at least in my time, a (symbolic) dress, who, wearing one, climbs a mountain or presides in church?

Nevertheless, I love being a woman and hope that is evident in my poems. And, although I have some regrets—the biggest being that I didn’t go on to graduate school, even at the coaxing of an admiring professor who would have waived the requisite entrance exam— I was just too exhausted—I am a satisfied, happy, old (in age only) woman. I write poems about my continuing relationships with my children and, now, grandchildren; about the continuing interchanges that happen with married couples who never get it entirely right. I hope readers of We Wore Dresses can find themselves in my poems, in the celebration of an ordinary life.

We Wore Dresses

We wore them everywhere. Learned the lay of the land in them. They reigned in our closets Every day to school we wore them. On the tricky bars, stifling the urge to hang from the natural bend of our knees Scenting starch and cotton, we learned division in them, in sashes and wide hems, diagrammed sentences, driving pencils— our legs crossed stony tight because of them— down the dead-end streets where prepositional phrases and adverbs belonged. In dresses we were careful, won few scars or bruises, collected even fewer tales of swift licks, shattered bones. No scrabbling to the rescue in a dress, or scorching to home base. We played jacks with bouquets of skirt bunched in the V of our legs. Dresses covered intricate bodies: puffed-sleeve dresses, dresses with gathered skirts, pleats like Japanese fans. We were flowers: angel trumpets, fuchsia, inverted tulips. Lithe teenage bodies in baby dolls, twirly skirts, sheaths. We were lavished with long, elegant versions for balls and proms— satin and glitter, chiffon and shine. How exquisite we felt—our throats bared and blushed; the way, with our fingertips, we lifted the skirts like ladies. How disarmed we were, our soft flesh belted, an orchid stuck near our made-up faces, perfumed and pinned carelessly close to our hearts.

The poem "When We Wore Dresses" makes me remember that when I started school at age 6 12 in 1947, Mother made my dresses with underpants of matching fabric (which I wore over my underwear) so I could hang upside down on the tricky bars. She must have been remembering her own early school days.